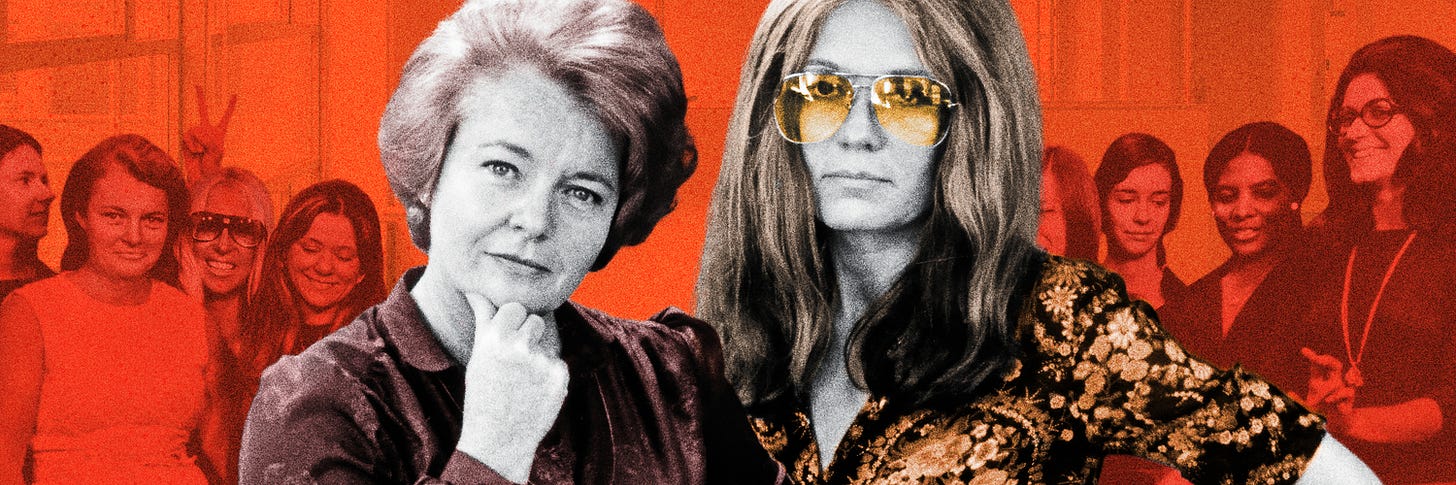

Dear Ms: A Revolution in Print

Interviews with Part 1, A Magazine for All Women: Salima Koroma Part 2, A Portable Friend: Alice Gu Part 3, No Comment: Cecilia Aldarondo

HBO and MAX on July 2, 2025

Describe the film for us in your own words.

Cecilia Aldarondo: DEAR MS is a formally ambitious and unconventional take on the second wave women’s movement and the pioneering magazine that witnessed it. Three directors were invited to tackle an aspect of Ms that spoke to us. In my case, I became very interested in the topic of pornography, how it tore the movement apart, and how Ms tried–and sometimes failed–to foster debate on the most divisive of feminist issues. It’s a story about infighting and factionalism in social movements, and what can go wrong when we don’t listen to the most vulnerable in our communities.

Alice Gu: Dear Ms. is film told in three parts about the iconic Ms. Magazine and its impact on second-wave feminism and the feminist movement, as a whole. In the spirit of magazine, each filmmaker was tasked to tell their part of the film using iconic covers, not unlike how various Ms. Magazine issues had different editors, each with it’s own point-of-view and aesthetic.

What drew you to this story?

Cecilia Aldarondo: I’ve always been a feminist. Ms figured heavily in my Gender Studies Masters degree. So when I got the call to direct Part 3, it was a no-brainer. Dream project.

Alice Gu: I’ve always identified as a feminist and I jumped at the opportunity to work with Gloria Steinem. It was an honor to be included.

Salima Koroma: Before Ms. Magazine dropped its first issue in 1972, women’s magazines were pretty much just beauty magazines. Publications like Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal taught women how to take care of a home, look after children, and look good for their men. But as Ms. co-founder Pat Carbine put it, “Women’s interests are much more profound than how to make meatloaf 12 new ways.”

The first issue of Ms. included articles like “De-sexing the English Language,” “How to Write a Marriage Contract,” “The Housewife’s Moment of Truth,” and “We Have Had Abortions,” pieces you’d never see in, say, Better Homes and Gardens. For the first time, women had a space to talk about what their actual lives were like and women across America wrote in to share their experiences.

But there were also missteps the magazine made. I was particularly interested in exploring the question: how do black women fit inside a magazine largely led by white women? I wanted to hear from the black women who wrote for Ms. Magazine and who were activists during the 70s what it was like to navigate both racism and sexism. What’s it like when the racial microaggressions are coming from inside the magazine?

I got to talk to Ms. contributor Michele Wallace–who wrote the book Black Macho and The Myth of the Superwoman–about her experience writing for the magazine (she had a mixed experience), and Marcia Ann Gillespie, who left Essence as Editor-in-Chief to run Ms. in the ‘90s. I also got to learn about Alice Walker’s time there, which was a bittersweet experience for her. Being able to explore the tension between black and white women was the first thing to draw me to this story.

What do you want people to think about?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Right now we are witnessing an authoritarian government trying to roll back everything the women’s movement has fought for. I would like viewers to think about what it took for the feminists who fought for our freedoms to achieve what they did, and how we can learn from them. I’m thinking a lot about the power of protest, and how nostalgic we can be when we see images of people taking to the streets back in the 60s and 70s. At a time when our freedoms of political expression are being so demonized, how do we take courage and fight with the same zeal of the women whose activism is now at risk of being erased? How do we learn from their mistakes, and make sure that our contemporary movements center the freedoms of the most vulnerable?

Alice Gu: It’s easy to forget in day-to-day life for women that many of the liberties and rights we have were not always available to us. Today, we’re able to open bank accounts and we’re able to assume that being sexually harassed at work is not acceptable. But, not that long ago, these things weren’t a given. I hope that viewers can reflect upon how things were and what work we still have to do.

Salima Koroma: I directed part 1 of the documentary, and titled it “A Magazine for All Women” because that was sort of the goal of the publication–to make a magazine for women. The idea is inspiring, but what happens when you have to implement that? What happens when one woman’s freedom is another’s confinement?

Marcia Ann Gillespie makes this point in a 1976 interview: “I hear white women talking about the need to fulfill themselves with meaningful work and getting out of the home, and I always say to them, ‘I just wish black women had the choice to stay home and raise children if we wanted to because that’s something that’s always eluded us. We have been workers. We are workers. Our problem is that we work in menial jobs so we don’t get enough money for what we do.’ There are differences that really have to be looked at.”

I want people to think about who we’re talking about when we say “all women,” and how we achieve something that acknowledges these intersectional differences.

What was the biggest challenge in making this?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Keeping my section short! There are so many fascinating people in the porn debates and the modern sex positivity movement that I would have loved to highlight. I feel like I just scratched the surface and I hope viewers research the women that are featured.

Alice Gu: Hunting down the photographers and graphics designers was a challenge. Many had passed away already, and their archives were lost. I wanted a very tactile, authentic feel for all the visual materials in the film, evocative of the time period. We did alright, in the end, but ther were many treasure we hunted for, but were never found.

Salima Koroma: This was a format I’d never done before. I was co-directing a film with two other women whose interests were different from mine. Normally, before starting a film, I do a ton of research then make an outline. I generally know where most of the film is going from beginning to end. For this one, I didn’t have a clue where the film was going. How do I start a film when I don’t know where it’s going to end? It was mind bending at first, but eventually, I let go of the need to know, and trusted my co-directors and the process at large.

What was the development process? How did you get green lit?

Salima Koroma: I had just finished directing a tech film for HBO when Dyllan McGee of McGee Media reached out to me. She told me about some projects she’d worked on, including one called Makers: Women Who Make America. I knew of Makers because my teacher and mentor Betsy West, Executive Produced the project. In fact, while I was working on my grad thesis, I’d pass by the edit bays and see Betsy watching down edits of Makers and stop in to watch with her.

So when Dyllan reached out and told me about a Ms. Magazine project, I knew it would be great. Normally I’d have to pitch the idea to a bunch of different networks and get them on board, but this project was already sold to HBO and had an anniversary tied to it: the 50th Anniversary of Ms. The fact that it was already sold was a huge plus.

What inspired you to become a storyteller?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Someone told me years ago that I ‘have an overinflated sense of justice.’ I take that statement as a compliment! I guess I have always had strong opinions about how art can help right the wrongs of this world. Plus, I don’t really like being told what to do and being a filmmaker is a pretty fulfilling way to do your own thing… so long as you are willing to fight a lot of battles to do it.

Alice Gu: There are so many stories out there that deserve to be told. I suppose I’ve always been a storyteller, as early as middle school, with my early affinity for photography. I won a photo contest in the 7th grade and realized that my images moved people.

Salima Koroma: When I was 11, I used to download a bunch of TV clips from Limewire and edit them to music on Windows Movie Maker. My entry into storytelling started in the edit. I love editing more than anything, because that is where the magic happens. That love for editing naturally made its way into filming my own stuff. By age 13, I was filming my friends and me performing skits around school. One of my skits made it to one of the school’s video broadcasts and I got such great feedback that I never stopped.

After 9/11 I got more into politics and social issues. The world began to change around me. My skits turned into interviews and I realized that speaking to people helped me understand the world a lot better. That, coupled with my undying love for the edit, steered me towards documentary storytelling.

What’s the best and worst advice you've received?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Best advice: find your people, remember your values, and stick to your vision. Worst advice: be agreeable and don’t speak up for yourself.

Alice Gu: Best advice: make a film that you want to make, because then at least one person in the world will like the film…you. Worst advice: I don’t think I listen to bad advice! I’m sure I received some bad advice at some point, but didn’t keep it in my head.

Salima Koroma: Best advice: surround yourself with people who trust your vision. Also stay on top of your taxes. Worst advice: Get everyone’s opinion.

What advice do you have for other female creatives?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Find your peers and collaborate. Filmmaking is next to impossible, and you’re best off if you have people to bounce ideas off of, to pick you up when you’re down. And don’t be a jerk–you don’t need to elbow people out of the way to be successful. Leave that bad behavior to the boys.

Alice Gu: Stay curious.

Salima Koroma: Tell stories that you actually care about. Right now, it’s hard to sell documentaries, at least from what I’m noticing. If you’re going into pitches sincerely excited and enthusiastic about your story (and it’s a good idea!) people can feel that. Don’t feel as if you have to cater to ideas you think will “sell”. Make a film you want to see.

Name your favorite woman directed film and why.

Cecilia Aldarondo: I don’t believe in ranking female directors or the films we make–there has to be room for more than one. Here are some that continue to guide me: El Velador by Natalia Almada, El Lugar Más Pequeño by Tatiana Huezo, Agnes Varda’s The Gleaners and I, Jeanne Dielman by Chantal Akerman, The Piano by Jane Campion, Cèline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Clueless by Amy Heckerling, Martha Coolidge’s Not a Pretty Picture… I can go on…

Alice Gu: Diary of a Teenage Girl by Marielle Heller

Salima Koroma: I have a few, but one of my all-time faves is a documentary called American Dream, which was directed by Barbara Kopple, and which won the Oscar for best documentary feature in 1991. The film is about a town in Minnesota, whose residents were employed by a meatpacking plant, and when they were forced to take pay cuts despite soaring profits, they went on strike. This film is a testament to the old school, verite docs that spent years following a town or niche group of people.

I love this film because it tells the story of America. We watch families who spent generations working in a meatpacking house lose everything to corporate greed. It’s not just a film that tells us how capitalism hurts Americans, it shows us in real time with real people who we come to care for.

In the past, verite films like American Dream (and Paris is Burning, and Harlan County USA, and Hoop Dreams) would take years to make. My first film took 3.5 years to make, and I loved every minute of it. You really get the chance to see a story play out. It’s hard to make a doc film like that now. Most documentaries these days are made in the span of 7 or 8 months. The entire landscape of documentaries has changed.

Feel free to share anything else you would like people to know about this film.

Cecilia Aldarondo: Don’t expect a straight comprehensive history. Instead, these are three distinct windows into the rich Ms story. Best to take each section as a unique fragment of a prism that refracts on the others.

Alice Gu: Please, enjoy!